“. . . Picasso changed or was changed, from a capital painter, known as such a painter should be known, into a monstre sacré, a holy cow surrounded with an enormous, self-perpetuating, inescapable, and generally irrelevant notoriety. And whereas a capital painter may be a man among other men, of finer essence no doubt but still capable of bleeding when pricked, a sacred monster may not; and when he is pricked he must ooze gold rather than blood, or at least a kind of contagious fame. To the natural inequality between him and most men is added a factitious and often somewhat tawdry rank: he is never allowed to forget his status and he must live almost as lonely as the phoenix, surrounded by courtiers rather than friends . . .”

- Patrick O’Brian, Picasso: A Biography

“The expression monstre sacré cannot be applied to many people. We could say this very expression has been invented for him [Alain Delon].

- Thierry Frémaux, Director of the Cannes Film Festival

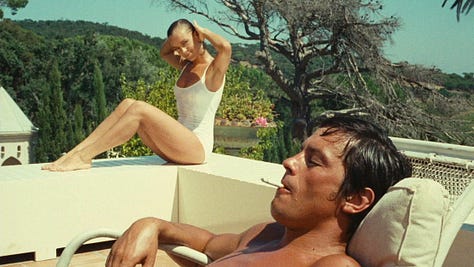

Since Alain Delon’s death last month, there has been an outpouring of tributes, commentaries, and criticism. Many writers have waxed poetic about Delon’s beauty, and who can blame them? I’ve often been guilty of doing the same. I’ve written quite a lot about my appreciation of Delon, who has long been one of my favorite screen actors, but I had trouble finding the words to say goodbye. I suppose a part of me wasn’t ready to let him go.

Along with an outpouring of praise for his screen accomplishments, some have used the opportunity to accuse Delon of being a mediocre performer with limited range. But this critique reflects more poorly on his critics than the actor, because if you’ve seen many of the films he appeared in, you’d know that he was often a brilliant performer with incredible depth.

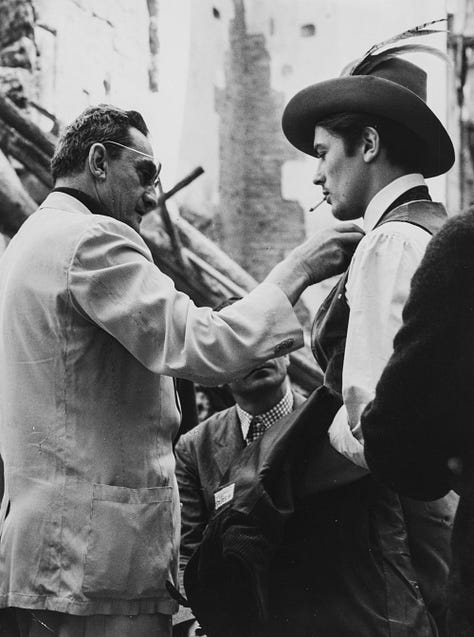

Delon was brilliant enough to be called “France’s James Dean” at the beginning of his career, and for good reason. Both actors were easy on the eyes, but they also delivered some of the screen’s most powerful and gut-wrenching moments. Don’t believe me? I dare you to watch Rocco and His Brothers (1960) and walk away without being in awe of what Delon does with that role. And that’s just one film of many where his natural charisma, innate acting abilities, and empathy with working-class characters brought out his best qualities.

Few actors, besides powerhouses like James Dean and Marlon Brando, knew how to faultlessly convey the inner turmoil of bitterly angry but oh-so-beautiful young men who desperately wanted to get ahead in life and were doomed to fail. Delon’s most enduring characters ached for a world that would provide them with more than pain, poverty, and struggle but quickly discovered that no matter how tough, smart, and attractive they might be, escaping your working-class background and avoiding the school of hard knocks is rarely possible. When you start life at the bottom the world will lift you up only so high before you feel the boot on the back of your neck.

At his best, Delon, much like Dean, always conveyed pain. It was the pain of that boot on the back of his neck. It was the pain of seeing the world without the benefit of rose-colored glasses. It was the pain of bitterly wanting a life that would always remain out of reach. That knawing hunger for more than the world could ever provide has moved many creative artists, but few have been able to bring it to the screen as succinctly as Delon.

As an actor, he made the decision to avoid the easy route that his looks could provide him. Instead of spending his career portraying handsome Romeos in light dramas and comedies or slick adventure seekers winning hearts and fortunes, he typically played loners, criminals, and losers. Deeply troubled men wrestling with modern malaise who rarely made it out of a film alive were Delon’s specialty. These were the characters he had a natural affinity for. His effortlessly cool persona and class consciousness were things that can’t be taught in acting school. You either have it, or you don’t, and very few actors have it. As a result, he became the quintessential French anti-hero at a pivotal time in history when filmgoers around the world were becoming weary of American heroes in white hats. Audiences flocked to theaters to watch Delon, a dark moody outsider who reflected their fears and frustrations. His exotic visage suggested faraway, unreachable places and otherworldy shores. It also conveyed a deep, unspoken wound. A knife cut so deep that it had chipped the bone. A bruise so violent that it left a monstrous scar.

This inner wound, this inner monster, is what made Delon such as fascinating screen presence. He didn’t need endless monologues and exaggerated mannerisms to convey deep emotion. When you watch him, you must wait patiently for the reveal of that festering wound, that inner monster. And it eventually shows itself in a piercing glance from his icy blue eyes or the clenching of his magnificent jaw. It’s not surprising that the French media has taken to calling Delon their monstre sacré (sacred monster or holy monster). Along with playing wounded monsters on screen, he has often been accused of playing a monster in his personal life.

After Delon died, social media sites like X (formerly known as Twitter) and Facebook were overrun by claims that Delon was a “misogynist,” “fascist,” and “homophobe.” Most of these accusations stem from a 2019 campaign by #MeToo activists who attempted to stop Cannes from awarding Delon an honorary Palme d’Or for his career in cinema. Thankfully, they didn’t succeed, and film critic Lisa Nesselson did a good job of dismantling their attack in a piece titled Honoring Alain Delon in Cannes Was The Right Thing To Do, Here’s Why. But the accusations against him have persisted, so I decided to tackle them myself.

The Failed Family Man

Alain Delon was born in 1935, and like many men from his era, he had trouble with fidelity. At times, he seemed to take pleasure in breaking hearts and was known to treat women rather coldly. But his most publicized romances with beautiful and talented women, such as Romy Schneider, Nathalie Delon, and Mireille Darc, flourished under the spotlight because Delon respected their acting abilities and insisted on casting them in the movies he was making. Even after his breakups, Delon typically maintained friendships with women and supported their careers, suggesting he valued them for more than just their physical assets. Delon has also openly credited the females in his life for his success, saying:

“If I hadn’t met the women I met, I would have died long ago. It’s the women - I don’t know why - who loved me, who got me into this profession, who wanted me to do it, and who fought for me to do it.”

Along with frequently praising the ladies in his life, he has also made some sexist, and extremely old-fashioned statements about women in the military. But more serious accusations came from his youngest son, Alain-Fabien Delon, who claimed that Delon beat his mother (Rosalie van Breemen) and sent her to the hospital with a busted nose and broken ribs. Delon publicly denied the accusations (although he admitted to slapping her) and accused his youngest son, who has struggled with drug addiction and financial issues, of lying for tabloid money. No formal charges were ever filed against Delon and no further evidence was provided, such as medical records that would be easy to verify. But that hasn’t stopped the press from running stories about the claims.

There is plenty of evidence to suggest Delon was not a good father, especially towards his sons who have publically aired their grievances. The actor, who was treated poorly by his own parents, was the product of a broken home and suffered severe emotional neglect which he admitted to internalizing. As a result, he sadly treated his own sons in a similar fashion by withholding affection and financial support. This was especially evident in the cruel way he rejected the son he had with renowned musician and actress Nico, whom he refused to acknowledge. Being the product of a broken home and having an undeniably rough start in life doesn’t excuse him, but it does shed light on Delon’s behavior and helps explain that inner wound he was harboring, which he often spoke about and expressed on screen.

Sexual Ambiguity

During his career, Delon played gay characters in Purple Noon (1966) and Swann in Love (1984) at a time when it was deeply unpopular and dangerous to do so. And although he had many widely reported romances with women, rumors that he had sexual relationships with men dogged him is entire life. When he was confronted in a 1969 interview by a British reporter who asked him if he had “homosexual tastes," Delon bluntly responded:

“So what’s wrong if I had? Or if I did? Would I be guilty of something? If I like it I’ll do it.”

Despite Delon’s instance on skirting around the issue, there is evidence to suggest that he may have had male lovers in his lifetime, including the film director Lucino Visconti, with whom he made some of his greatest films. Even if his relationship with Visconti was purely platonic, the two men remained extremely close until Visconti’s death, and Delon regularly expressed his affection and admiration for the openly gay filmmaker.

Delon, who was nearly 90 years old when he died, rose to fame when being homosexual or bisexual could land you in jail or destroy your acting career. It should surprise no one that he may have kept his sexuality under wraps or wasn’t particularly forthcoming about all his bed partners. Any homophobic statements he made late in life concerning gay couples being allowed to adopt children should be considered in this light. Thankfully the times have changed but Delon, like many of his generation, had to navigate the homophobia of his era, and it undoubtedly colored his views. It may have also kept him in the closet.

Political Filmmaking

The most dangerous accusation being flung at Delon is that he was a fascist. This is mainly the result of his lifelong friendship with right-wing politician Jean-Marie Le Pen (father of Marine Le Pen) whom he met during the Indochina War when both men were serving in the French Foreign Legion. Delon was just 17 years old at the time and the friendships he formed on the battlefield undoubtedly left an impact. But Delon, who was a fervent Gaullist, never campaigned for Le Pen and his far-right National Front party, despite saying he had:

“points of agreement and disagreement with Jean-Marie Le Pen. He has long been a friend whose company I enjoy. Full stop.”

For some, Delon’s association, along with his praise for Le Pen, makes him a fascist but it is important to point out that the actor’s friendship with the far-right politician did not impact the creative choices he made.

Throughout his career, Delon not only acted in anti-fascist films such as The Unvanquished (1964), Is Paris Burning? (1966) and Mr. Klein (1976), but he also funded their production. In The Unvanquished, which was a passion project for the actor, Delon plays a French Foreign Legion deserter in Algeria at odds with the military who risks his life to save a communist lawyer from the OAS, a notorious far-right French paramilitary group. In Is Paris Burning?, Delon portrays a member of the French Resistance fighting Nazis, and in Mr. Klein, another film set in Paris during the German occupation, Delon plays an art dealer mistaken for a Jewish man who finds himself on a train headed for Auschwitz. All these films were made in association with directors, writers, and other creatives who were communists or radicals.

At the time that these powerful political films were released, France was still struggling to acknowledge the horrors they were responsible for in Algeria and during WWII. Delon’s commitment to making anti-fascist and anti-war films that criticized his country was met with both critical and political pushback, but he endured. His creative accomplishments as an actor and producer in this arena should not be ignored or overlooked. They should be acknowledged and celebrated.

Did Delon say some terrible things? Absolutely. Did he keep some questionable company? No doubt about it. Did he treat some of the people in his life heartlessly? Definitely. But throughout the actor’s very public life, he generously gave a lot of his time and resources to animal welfare organizations, AIDS research, the Global Gift Foundation, and UNICEF, among other charities. Unfortunately, his impressive philanthropy doesn’t get as much attention as his human failings, which is a terrible shame.

Today, there is a lot of focus placed on an artist’s behavior, morals, and personality traits. Unless you’re an angel, you will be judged as a devil. And most artists worth a damn have a bit of the devil in them. Delon was no angel, despite earning the screen moniker of "ice-cold angel," and his questionable statements, behavior toward women, as well as his relationships with far-right figures, deserve to be examined. But the man wasn’t some cartoon monster who should be shunned. He was a complex and deeply flawed human being with extraordinary gifts who did some exemplary charity work. A monstre sacré.

Terms like “misogynist,” “homophobe,” and especially “fascist” are now being flung around so freely that they’re beginning to lose all meaning, and that’s extremely troublesome. In the highly politicized atmosphere we’re all navigating, we should be very cautious about who and what we label fascist. By casually using the word, we lessen its impact and muddy its meaning. The result is a dumbing down of our political discourse that gives cover to real fascists as well as modern-day fascism, which is on the rise.

Combat fascism by watching and sharing The Unvanquished, Is Paris Burning? and Mr. Klein, which showcase Delon’s talents and make a wonderful triple bill.

Vive la Alain Delon!

Links to my writing on Delon and his films:

The Last Film of Julien Duvivier: Diaboliquement Vôtre (1967)

Some Thoughts on Jack Cardiff’s The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968)

Obituaries: