We live in the age of remakes, sequels, and prequels. Every year, Hollywood churns out easily recognizable titles that have been repackaged and recast, often with plots that feel all too familiar. The horror and science fiction genres have been hit particularly hard by this wave of reimagined films, which often fall short of the original productions they’re trying to ape. But occasionally, a talented director such as John Carpenter (The Thing, 1982), Philip Kaufman (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1978), or David Cronenberg (The Fly, 1986) comes along and remakes a classic that’s as compelling as its predecessor. Notice I didn’t say “better” than the original—because that is rarely the case—but a good remake can bring something unique to the table, allowing audiences to view the original with fresh eyes. A great remake stands on its own as a gripping piece of cinema. Unfortunately, today, too many filmmakers lean heavily on nostalgia and familiarity, often at the expense of creativity and innovation.

One of my favorite remakes is Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht, 1979), a reinterpretation of F.W. Murnau’s silent-era masterpiece. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), with its imaginative visuals and haunting aesthetic, holds a revered place in the horror pantheon. But in 1979, Herzog reintroduced the tale to contemporary audiences, imbuing it with his distinct style and modern concerns. Herzog’s decision to revisit Nosferatu was deeply personal. He was part of the New German Cinema movement, a post-World War II artistic resurgence aimed at redefining German filmmaking. As the director explained in the book Herzog on Herzog: Conversations with Paul Cronin, he believed that authentic German cinema had vanished when Hitler came to power in 1933. He regarded Nosferatu as the greatest German film ever made and sought to bridge Germany’s fractured cultural history by reinterpreting Murnau’s film. In Herzog’s view, modern Germany was “a fatherless generation” in need of continuity—a filmic connection to a past not overshadowed by the atrocities of war.

In an era when many classic films are just a mouse click or finger swipe away, it’s easy to forget how inaccessible Murnau’s Nosferatu was to a new generation of filmgoers in 1979. Beyond its silent format, which modern viewers often find antiquated, the film carried the weight of its historical context—a reminder of a past that postwar Germany yearned to leave behind. German youth were especially eager to remake their country in the aftermath of WWII and in the process, some overlooked or rejected the artistic accomplishments of their ancestors. Herzog’s remake, however, served as both homage and reinterpretation. He hoped his film would showcase his sincere reverence for Murnau’s original which he conceived as a tribute. Although he would go on to mimic many of Murnau’s directing choices, Herzog also made noticeable changes to the script that allowed him to address his own artistic concerns.

Herzog’s film uses Murnau’s work as a springboard while exploring new thematic territory. In some respects, it surpasses the original; in others, it falls short. For instance, I prefer the way that Murnau handled the character of Renfield, and many of his framing shots and close-ups are so perfectly executed that they can’t be surpassed. On the other hand, I prefer how Herzog handled the overall story arc. His decision to make the townspeople more complacent with a monster in their midst, while insisting that evil doesn’t just disappear but merely finds a new guise, is particularly poignant. This is especially true when you consider Germany’s own experience with very real historical monsters.

Herzog’s film is also brimming with beautifully staged scenes that are equal to anything found in Murnau’s film but reflect his unique directing style and distinct vision. Few filmmakers integrate natural and urban landscapes as effectively as Herzog, and in Nosferatu, even the plague-ridden rats possess a strange, ornamental beauty. Herzog’s film is exceptional for the way it masterfully updates a genre-defining silent film without losing any of the original’s power or mystique.

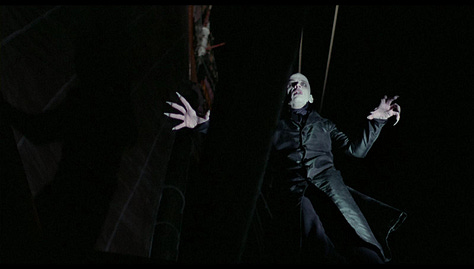

One of Herzog’s most inspired choices was casting Klaus Kinski as Count Dracula, which was a role previously inhabited by Max Schreck. Kinski makes a formidable vampire and his dynamic working relationship with the director undoubtedly colored his performance. Kinski’s interpretation of Dracula is transformative, imbuing the undead creature of the night with unexpected humanity and inherent grace. Instead of simply mimicking Schreck, Kinski’s Dracula exudes a tragic pathos reminiscent of the tormented creatures from Universal’s classic horror canon, such as Frankenstein (1931) and The Wolf Man (1941). As a result, it’s one of the actor’s most fascinating and oddly touching performances. In his autobiography, Kinski Uncut, the actor described the transformative physicality of the role, from shaving his head to embodying the vampire’s emotional vulnerability.

“The departure point is Munich. Four weeks before shooting starts, I have to fly there for costuming. And this is where I shave my skull for the first time. I feel exposed, vulnerable, defenseless. Not just physically (my bare head becomes as hypersensitive as an open wound) but chiefly in my emotions and my nerves. I feel as if I have no scalp, as if my protective envelope has been removed and my soul can’t live without it. As if my soul has been flayed. . .At first I go outdoors only when it’s dark. Besides, I wear a wool cap all the time even though it’s spring. You may think ‘So What? Some guys are bald.’ But the two have absolutely nothing to do with one another. What I mean is the simultaneous metamorphosis into a vampire. The nonhuman, nonanimal being. That undead thing. That unspeakable creature, which suffers in full awareness of its existence.”

– Klaus Kinski, Kinski Uncut

Kinski’s performance is matched by his co-star Isabelle Adjani’s haunting portrayal of the ethereal Lucy Harker. Like the silent actress Greta Schröder, Adjani’s otherworldly beauty and expressive eyes tell the audience all they need to know about her tragic and conflicted character. Bruno Ganz also delivers a subtle yet powerful performance as the doomed Jonathan Harker whose sad descent from devoted husband to bloodthirsty monster underscores the film’s themes of corruption and loss.

Since its release, Herzog’s film has divided audiences and critics. Some find it a better and more fully realized film than the original while others, such as author David J. Skal who wrote Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula (often referred to as the ‘definitive’ history of Bram Stoker’s Dracula) called Herzog’s film, “A wrong-headed and rather pretentious remake.”

Regardless of where one stands, I can’t imagine being indifferent to the images that Herzog summoned from the depths of his imagination in homage to Murnau. There’s a brilliance as well as a majestic quality to his reimagining of a classic that I find undeniable. Nosferatu the Vampyre is not merely a remake but a reverent dialogue with its predecessor—a film that bridges eras, challenges perceptions, and lingers in the imagination like a malignant specter. Conjuring up new nightmares from the smoldering ashes of the old world it is desperately trying to leave behind.

You can currently find Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre streaming for free on Kanopy and Tubi.

Note: This piece was originally published on TCM.com and I’ve updated it for Substack.

You are right about those three other remakes! I haven't seen this one, and so I put it on hold at the lie berry. Remakes nowadays are so horrible. By nowadays I mean since 2000 at least, and The Manchurian Candidate and The Stepford Wives remakes are what cemented this prejudice. I didn't bother to investigate Invasion of the Body Snatchers #3 for this reason.